By Michael Noel, Founder of DeReticular.com

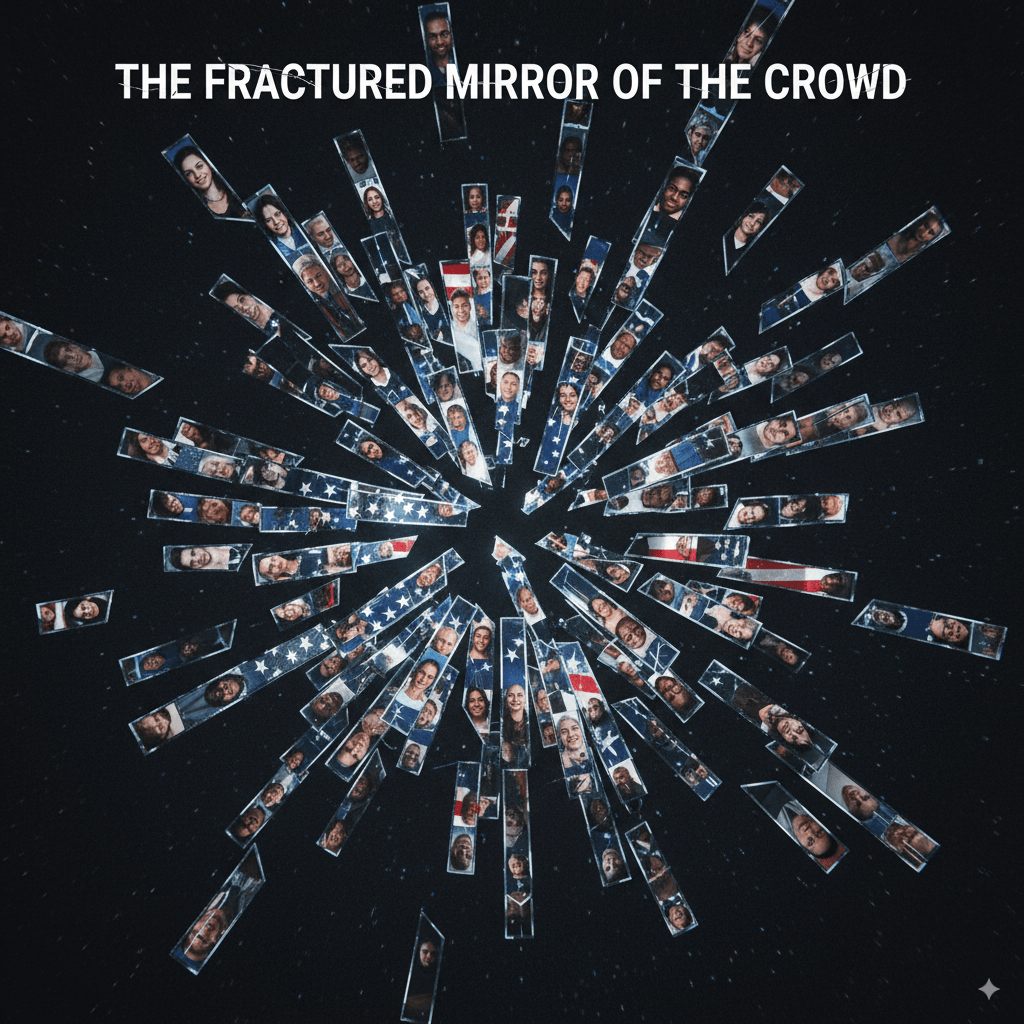

There’s a prevailing belief, a comforting notion, that the collective judgment of a diverse group—the “wisdom of the crowd”—will invariably guide us toward a more perfect union. It’s a cornerstone of the American experiment. Yet, as we navigate the turbulent currents of the 21st century, we find ourselves a nation increasingly at odds, a society fractured along lines of political ideology and geographic happenstance. The question is not whether the crowd is wise, but whether the crowd is even being heard.

Two insidious forces, gerrymandering and redlining, have systematically dismantled the very framework upon which collective wisdom is built. One, a tool of political expediency, and the other, a legacy of institutionalized prejudice, have colluded to create a divided America where the voices of many are silenced, and the interactions between us are irrevocably altered. These are not abstract concepts; they are the architects of our present discontent, and their blueprints are etched into the very fabric of our communities.

Gerrymandering: The Art of the Echo Chamber

The principle of “one person, one vote” is fundamental to our democracy. However, the practice of gerrymandering—the manipulation of electoral district boundaries to favor one political party—has rendered this principle tragically quaint in many parts of the country.[1] Through the sophisticated use of “cracking” (diluting the voting power of an opposing party across many districts) and “packing” (concentrating an opposing party’s voters into a few districts), those in power can effectively choose their voters, rather than the other way around.[1][2]

This strategic cartography does more than just secure political power; it fundamentally alters the political landscape. By creating “safe” districts where incumbents face little to no competition, gerrymandering disincentivizes moderation and compromise.[3] Representatives in these districts are more beholden to the ideological extremes of their base than to the broader electorate, leading to increased political polarization.[4][5] The result is a Congress and state legislatures filled with individuals who have little reason to engage with opposing viewpoints, effectively creating echo chambers where the “wisdom of the crowd” is replaced by the roar of a carefully curated mob.[3][4]

A stark real-world corollary of this can be seen in states like Wisconsin and Michigan, where heavily gerrymandered maps have allowed legislatures to pass laws that are out of step with the majority of the state’s population.[6] In Michigan, for instance, gerrymandering was cited as a contributing factor to the Flint water crisis, as it insulated officials from the political consequences of their decisions.[6] This is the antithesis of a responsive government guided by the collective will of its citizens.

Redlining: The Architecture of Division

While gerrymandering manipulates the political map, redlining has for decades distorted the physical and social landscape of America. This discriminatory practice, institutionalized in the 1930s by the federal government and the real estate industry, designated minority neighborhoods as “hazardous” for investment, effectively denying residents access to mortgages and other financial services.[7][8] Though outlawed for over 50 years, the legacy of redlining persists with devastating consequences.[9]

The long-term effects of this systematic disinvestment are stark. Formerly redlined neighborhoods are still predominantly populated by minority communities and suffer from lower homeownership rates, depressed property values, and a significant wealth gap.[7][10] This has created a deeply entrenched system of racial and economic segregation.[11]

But the impact of redlining extends beyond the economic sphere. These neighborhoods are more likely to be “food deserts” with limited access to fresh and healthy food.[8] They also experience higher levels of environmental pollution, with a greater proximity to industrial sites and hazardous waste.[12][13] This environmental racism has led to measurable health disparities, including higher rates of asthma, cancer, and other chronic illnesses in formerly redlined communities.[9][13]

The very way we interact with one another has been shaped by these invisible lines drawn decades ago. By concentrating poverty and limiting opportunities, redlining has created physical and social barriers that inhibit the kind of diverse, cross-cultural interactions that are essential for a healthy society and a truly “wise” crowd.

The Unraveling of the American Tapestry

Gerrymandering and redlining are not separate issues; they are two sides of the same coin of division. Gerrymandering often leverages the residential segregation created by redlining to more effectively “pack” and “crack” voting districts along racial and partisan lines.[3] The result is a vicious cycle: segregated communities are more easily gerrymandered, and gerrymandered districts are less likely to produce representatives who will address the systemic inequalities born from redlining.

This self-perpetuating cycle contributes greatly to a divided America. It fosters an “us versus them” mentality, both politically and socially. When our elected officials are not accountable to a diverse constituency, and when our neighborhoods are homogenous by design, the “other” becomes a caricature, a political talking point rather than a neighbor. The wisdom of the crowd is lost because the crowd has been atomized, its collective voice fractured into a cacophony of isolated interests.

A Call for a New Blueprint

At DeReticular, our guiding principle is that you can’t sail today’s boat on yesterday’s wind. The systems of gerrymandering and redlining are the antiquated vessels of a bygone era, and they are steering us toward the rocks. To navigate the complexities of the modern world, we need a new approach, one that is decentralized, transparent, and empowers communities from the ground up.

The solutions to these deeply entrenched problems will not come from the top down. They will be built by local leaders, by innovators, and by engaged citizens who are willing to draw new maps—not of division, but of collaboration.

This is a call to action for Rural Teams across the country who are looking to positively affect their local communities. We are seeking partners who are developing innovative, localized solutions to bridge the divides created by these historical injustices. Whether you are working on community-owned internet infrastructure to close the digital divide, developing new models for affordable housing, or creating platforms for civil discourse that transcend partisan divides, we want to hear from you.

The wisdom of the crowd is not a myth, but it is a resource that must be cultivated. By dismantling the structures of division and building new systems of connection, we can once again harness our collective intelligence to build a more equitable and prosperous America for all. Let us be the architects of a future where every voice is heard, and every community has the opportunity to thrive.

Sourceshelp